I saw this in an obituary this morning:

Sylvia always brought so much food to family events that people had to make several trips to her car to bring it all in.

Kind of a poem about a certain slice of North Carolina in the mid-20th Century.

MidLaw and Divers Items

MidLaw and Divers ItemsI saw this in an obituary this morning:

Sylvia always brought so much food to family events that people had to make several trips to her car to bring it all in.

Kind of a poem about a certain slice of North Carolina in the mid-20th Century.

We are at a cultural moment.

We are at a cultural moment.

Sexual boundaries seem to be the “acutest issue” of the moment.

These are not new questions to North Carolina. This moment is not the first.

In Greensboro in 1878, Quaker editor David Swaim thundered in Greensboro’s leading newspaper: “Blast the prejudice that puts women down as only fit to be men’s playthings!”

His conservative counterpart, former Supreme Court Justice and founder of the UNC Law School, William Horn Battle rejoined: “No Southern lady should be permitted to sully her sweetness by breathing the pestiferous air of the courtroom.”

They were arguing about whether women should be permitted to practice law.

The issue was joined in Greensboro and taken to Raleigh. Leading North Carolina legal figures of the day took up the question: Albion Tourgée, William Horn Battle, Richmond Mumford Pearson.

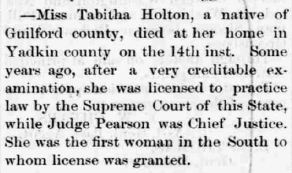

It is the story of Jamestown native Tabitha Holton who became the first woman lawyer in the South.

A circular published when Holton died proclaimed:

The power of thy genius has broken the iron bands of brutality which had been rivited [sic] for ages upon thy sex. No more can the barbed shaft of prejudice and envy reach thee in thy eternal repose.

First in all the Sunny South to claim, and obtain, the full rights of womanhood

Tabitha Holton’s story is fabulized here. Her victory, which upset the custom and practice of centuries, was, in the end, based on merit. Opposition based on her status as a woman failed to stand against her unquestioned merit as a lawyer.

My North Carolina heritage started in the mid-18th Century. After about 1760, my ancestors are from North Carolina all the way down.

Some of them were slaveholders, most not.

One, from Perquimans County, is identified as the first person in North Carolina to have liberated all his slaves because he concluded that slavery itself was immoral. Another, said to be the largest slaveowner in Guilford County, provided for his slaves to be liberated upon his death. This provoked litigation (to the Supreme Court) contesting his will by his disappointed son. His widow, evading local law enforcement, took off with the people to Ohio.

Others included founders of the North Carolina Manumission Society, secret participants in the underground railroad (a participant as best I can tell, it was secret after all), and abolitionists.

But, still others continued to hold slaves. And probably more than anything else my forebears were small farmers, laborers, teachers, and lawyers, preachers. One was an indentured servant.

When war came, two were Confederate officers: one was killed in a daring charge; another served for an initial term, then returned home to his family in Randolph County. Two more were private soldiers, one of whom spent much of his war as a prisoner, while the other one got trounced at Gettysburg then nearly starved to death on a long, solitary walk back to Edgecombe County.

Others opposed the war. One paid the fee that exempted members of peace religions from military service. He provided succor to deserters and escaped POWs for whom Guilford County was a gathering place. Another was imprisoned for refusing to serve in the Confederate army. He was tortured by his North Carolina neighbors at the infamous Confederate prison at Salisbury.

So, what is my heritage? What monument do I claim?

I am not unusual. North Carolina’s story was never one of united, unreserved support for the Civil War. It was never so simple.

Few, if any of us, tie back to only one narrative — or to a simple, narrow “heritage.”

Guilford College President Jane Fernandes recently posted on her blog a dynamite note titled “Moving from Safe to Brave.” It mirrored her remarks as a featured speaker at the 2017 Higher Ed Colloquium in Florida, a national program of the College Board.

Guilford College President Jane Fernandes recently posted on her blog a dynamite note titled “Moving from Safe to Brave.” It mirrored her remarks as a featured speaker at the 2017 Higher Ed Colloquium in Florida, a national program of the College Board.

That post puts me in mind of an earlier Guilford leader who chose “brave” over “safe.”

In the period immediately after Lincoln called for troops, “trouble and perplexity were in the air” at Guilford College and in North Carolina. War was coming. Many Quakers and others who opposed secession were leaving. At that point, New Garden Boarding School (later Guilford College) was full. Nereus Mendenhall was its Superintendant and the principal teacher. But Mendenhall owned property in Minneapolis and his brother-in-law urged going there. For Mendenhall, this promised “worldly advancement and the accumulation of wealth.” And, as a pacifist and abolitionist, he had concerns about raising his family in slave territory.

So, he and his wife, Orianna, packed their bags for Minnesota.

On the day before they were to depart, they went over to the school to close up. But when it came to closing the school and leaving the students, Nereus could not do it. Their daughter Mary later recalled both her parents standing at the library, weeping. Nereus said, “Orianna, if I feel that the Lord requires me to stay, is thee willing to give up going and stay here?” Orianna said, “Certainly, if that is thy feeling, I am satisfied to stay.”

So Nereus and Orianna made the brave choice, certainly not the safe one. They stayed.

Opposed to secession, opposed to slavery, and opposed to war, Mendenhall kept New Garden/Guilford open throughout the war. During that time, people associated with the College often gave food and shelter (refuge) to deserters, bushwhackers and escaped slaves.

Guilford was “the only school in the South that was not closed during the war or during reconstruction.”

From this evidence, it may be deduced that Guilford’s athletic teams must have gone undefeated during that period.

Brave. Undefeated.

The Mendenhall home, The Oaks, is for sale now by Preservation North Carolina and likely to be demolished.

NC Capitol

War came and North Carolina Quakers were in a bad spot. They were abolitionists and unionists and pacifists to boot.

A bill was introduced in the North Carolina legislature to require that every free male over sixteen years old must publicly renounce allegiance to the government of the United States and agree to defend the Confederacy. The penalty for noncompliance was banishment.

It was a bridge too far. Former governor William Graham, who Bishop Cheshire said was one of the greatest men North Carolina ever produced and who represented North Carolina’s traditions of progress and moderation, spoke against the bill. He said it would be “a decree of wholesale expatriation of the Quakers.” “The whole civilized world would cry ‘shame,’” he said.

And so the bill was defeated, although “not so the hostility” from which it came. “Hatred and malice … fell with much violence” upon North Carolina Quakers.

Virginia Capitol

Legislation was proposed at both the State and Confederacy levels to provide exemptions from military service for Quakers and other “peace churches.” North Carolina Quakers recruited a committee to go to Richmond and make their case to the Confederate government.

Among the five-person committee was Nereus Mendenhall, the leader of New Garden Boarding School (later Guilford College) in Guilford County. He was “well known as one of the most learned men in North Carolina and a prominent educator.”

At Richmond, they met with a committee of the Congress. It was summer and they met at night outside on the grounds of the Capitol. One of those present said later,

It was the feeling of the delegates that Nereus Mendenhall was preeminently the man to present our case. It seemed impossible, almost, to secure his consent, owing to his natural reserve. Finally, [the chairman] said: “Gentlemen, the Committee is ready. Please state your case.” A dead silence followed. In a few minutes, fearing the committee would not understand or appreciate our holding a silent Quaker meeting then and there, I reached over and gently touched Nereus. He arose slowly, and when fully aroused and warmed up to his subject I thought I never heard such an exposition of the doctrines of Friends on the subject of war.

Later, the group visited Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederacy. Davis received them courteously but remarked that he “regretted to learn” there was a group of people who were not willing to fight in defense of their country.

A statute was passed that exempted Quakers and members of other peace churches from military service upon either payment of money or rendering noncombatant services. A participant in the process said that

To Nereus Mendenhall’s argument, perhaps more than any other one thing, was due the passage of this law.

In later times, some Quakers refused to serve and refused to make payments or perform noncombatant services. Some of them were punished severely.

Mendenhall’s home, The Oaks, was located on what is now NC 68 between Greensboro and High Point in Guilford County. It is for sale by Preservation North Carolina and may be destroyed.

Nereus Mendenhall

The Oaks

Got to be Randall Jarrell, right?

Got to be Randall Jarrell, right?

Here’s proof. There’s this podcast from London, “Backlisted, a podcast giving new life to old books.” It’s these two Brits with a guest talking (fortnightly) about books. (Awfully good talkers. Listening to them talk is like watching real athletes play pick-up basketball. You might get in the game but you could never keep up.)

Anyway, in September the sixth show was about The Animal Family by Randall Jarrell, author, poet, critic, UNC-G professor and collaborator with illustrator Maurice Sendak. The extravagance of their appreciation for Jarrell made me wonder why we hear his name so little in Greensboro. Maybe we should have a statue of him to go with the O’Henry one. (O’Henry born here, left; Jarrell came here, stayed.) The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner.

Name somebody else from Greensboro (from NC) they’re talking about in London.

If not him, who?

Circulating anti-slavery literature was a crime punishable by imprisonment and a whipping in North Carolina in the years just before the Civil War and The Impending Crisis by Hinton Rowan Helper was the very definition of such literature.

Circulating anti-slavery literature was a crime punishable by imprisonment and a whipping in North Carolina in the years just before the Civil War and The Impending Crisis by Hinton Rowan Helper was the very definition of such literature.

Nereus Mendenhall, the Superintendent (president) of New Garden Friends School (which became Guilford College) and himself an abolitionist, owned multiple copies of The Impending Crisis which he made freely available to others. So Greensboro authorities determined to seize his books and put him in jail. They sent out a posse for that purpose.

But Mendenhall’s brother Cyrus, a Greensboro lawyer, businessman and the Treasurer of the North Carolina Railroad, had learned of the plan and sent word to his brother. More to the point, he also sent word to his to his sister-in-law, Orianna Mendenhall. Upon receiving the news, Nereus sat stolidly in his chair and refused to take any action. He continued reading. No so, Orianna. When she saw what Nereus was doing, she gathered up the books and threw them into the fire. Arrest averted. (Go Orianna!)

Mendenhall’s home and Orianna’s fire were on a farm known as The Oaks between Greensboro and High Point out on what is now NC Highway 68. The house where Mendenhall received his brother’s message and the room in which his books were burned are now for sale by Preservation North Carolina. The house was built in 1830 and is an architecturally significant example of a Quaker Plan house. If not sold, it will likely be destroyed.

Mendenhall’s home and Orianna’s fire were on a farm known as The Oaks between Greensboro and High Point out on what is now NC Highway 68. The house where Mendenhall received his brother’s message and the room in which his books were burned are now for sale by Preservation North Carolina. The house was built in 1830 and is an architecturally significant example of a Quaker Plan house. If not sold, it will likely be destroyed.

Richard Mendenhall

William Horn Battle

OK – now I am fascinated.

In Memories of an Old-Time Tar Heel, Kemp Plummer Battle recalls a trip that he and his father, William Horn Battle, made to Asheville in the summer of 1848. Kemp was sixteen years old. On the way, they stopped at Jamestown where they spent an evening with Richard Mendenhall, “an old acquaintance of my father.”

Here is part of Kemp Battle’s account:

Near Greensborough we met an old acquaintance of my father, a refined and educated Quaker named Richard Mendenhall. On parting, he said courteously, “Come and see me, Kemp, and I will entertain thee for thy father’s sake until I know thee and can entertain thee for thy own.” I afterwards found this was a quotation from Swift’s Tale of a Tub.

While Mr. Mendenhall did not keep a hotel, he was willing to furnish meals to travelers at his house in Jamestown (pronounced “Jimston”). My father and I had dinner with him. Some friends had told me that he was fond of testing their knowledge of history. I determined to put a bluff on him. He began by asking me what was a giaour, the title of one of Byron’s poems. I happened to know that it was a name given by the Turks to disbelievers in Islamism. I answered his question and at once plied him with counter historical questions so fast that he refrained from catechising me further.

A nice story. Old-time Tar Heels, indeed. You can visit the Mendenhall home in Jamestown today and see where they were.

But how did William Horn Battle come to be acquainted with Richard Mendenhall? They were an unlikely pair.

William Horn Battle was born and raised in Battleboro (then) in Edgecombe County, a town founded by his grandfather. His family were farmers and slaveholders and founders of one of the oldest cotton mills in the state, which operated with slave labor. Battle himself was a lawyer, banker, judge and North Carolina Supreme Court Justice. He is acknowledged as the founder of the UNC Law School. Conservative at his core, William Horn Battle was the very embodiment of the antebellum establishment. He prominently opposed licensing women to practice law. Son, Kemp, among other roles, was president of the Chatham Railroad Company, Treasurer of the State, and president of the University of North Carolina.

Richard Mendenhall was born and raised in Jamestown in Guilford County, a town founded by his father and named for his grandfather who settled it. Mendenhall operated what is now preserved as the Mendenhall Plantation. He was a tanner, merchant, and educator. He was also an abolitionist and a founder and president of the Manumission Society of North Carolina. He led in transporting African Americans to Liberia and Haiti. He is said to have been a principal in the Underground Railroad. His younger brother, George C. Mendenhall, was a prominent lawyer, legislator, and UNC trustee. George was a large slaveholder, who formed companies of slaves that operated variously as builders, caterers, farm laborers, etc. Under Richard’s influence, George and his wife transported their slaves to freedom in the Midwest, thereby stimulating celebrated litigation. As a lawyer, George defended abolitionists and free blacks. Richard Mendenhall’s sons were a lawyer, bankers, investors in cotton mills, and leaders in building the North Carolina Railroad. His son, Nereus Mendenhall, served as president and kept Guilford College open through the Civil War and afterward. Guilford College, when led by Mendenhall, has been characterized as an “island of moderation, surrounded by a sea of fundamentalism.”

Both the Battles and the Mendenhalls were Whigs and unionists. But, when war came the Battles were ardent supporters of the Confederacy. The Mendenhalls, Quakers, stood aside from the war. Some were imprisoned and abused for refusing to fight. Nereus Mendenhall interceded with Jefferson Davis to arrange legal protections for Quakers and other pacifists.

So William Horn Battle and Richard Mendenhall seem unlikely dinner companions. An eastern planter and a Piedmont abolitionist. Each might rather have regarded the other as a Carolina giaour, than as a dinner-table discussant of literature and history. (Sixteen-year-old Kemp Battle later became professor of history at UNC.)

MidLaw’s theory is that Battle and Mendenhall may have become acquainted in Raleigh, perhaps in connection with Richard’s service in the General Assembly (if he did serve, as MidLaw believes he did).

Or, it may have been that William Horn Battle and Richard Mendenhall were simply a pair of civil, cultivated people, North Carolina leaders, from different backgrounds and with different points of view in what was becoming an increasingly divided society. Old-time Tar Heels.

US Attorney General Loretta Lynch was on the Sunday AM news shows this morning to talk about the Orlando killings. She is very impressive.

US Attorney General Loretta Lynch was on the Sunday AM news shows this morning to talk about the Orlando killings. She is very impressive.

Fascinates me to know that her father is from Oak City. She was born in Greensboro.

No real significance to that, I suppose, but still …. More on the theme of notable lawyers from around here. Keeping the compendium complete.

Speaking at the Guilford College Bryan Series in Greensboro this week, Jon Meacham commented on Andrew Jackson, about whom Meacham has written a Pulitzer-Prize-winning biography. “Sorry,” he said to the Greensboro crowd, but “Jackson was a South Carolina native who settled in Tennessee.”

Speaking at the Guilford College Bryan Series in Greensboro this week, Jon Meacham commented on Andrew Jackson, about whom Meacham has written a Pulitzer-Prize-winning biography. “Sorry,” he said to the Greensboro crowd, but “Jackson was a South Carolina native who settled in Tennessee.”

Boy, did Meacham miss an opportunity. For two years before he left for Tennessee, Andrew Jackson lived and practiced law virtually on the spot where Meacham was standing as he spoke those words.

Jackson got his legal education clerking in Salisbury then moved to Martinsville, a now-extinct town in Guilford County (essentially, Greensboro), where he was first licensed to practice law. Later, he moved from Guilford County to Tennessee with Judge John McNairy of Horsepen Creek (now also part of Greensboro). McNairy was the first native-born lawyer licensed in Guilford County, and McNairy descendants still practice law in Greensboro, including one at Brooks Pierce McLendon Humphrey & Leonard. Both McNairy, a federal judge, and Jackson became leading figures in Tennessee.

Meacham, himself a Tennessee native and resident, missed a golden opportunity to pander to his Greensboro audience in the course of an otherwise excellent presentation focused mostly on his new biography of George H.W. Bush.