Tabitha Ann Holton’s story should be a movie. The only problem would be restraint. It’s the Zero Dark Thirty and Argo problem. Should factual accuracy stand in the way of fabulism?

Tabitha Ann Holton

The South’s first woman lawyer, Tabitha Holton, was the child of religious dissenters who settled in central North Carolina. Her father was “read out” of his Quaker meeting. He was educated as a lawyer but became a Methodist Protestant minister. Ultimately, he was too outspoken even for that anti-hierarchical and anti-slavery denomination and he led in forming an even more radical one.

Tabitha was educated at Greensboro Academy. She watched as her brothers studied law and then, in January 1878, she applied for a license herself, alongside her brother Samuel. But, the relevant North Carolina statute limited the practice of law to “persons” and so there was a controversy about whether that term included women.

At the time, only six states had admitted women to practice law, and roughly a dozen women had been licensed in the entire country. None in North Carolina; none in the South.

North Carolina’s Supreme Court asked for oral argument. The newspapers took up the issue. Iconic figures aligned on each side: William Horn Battle for tradition vs. Albion Tourgée for Tabitha.

Battle was the archetypical Southern CONSERVATIVE; Tourgée, the RADICAL. Tradition vs. change. What price progress?

William Horn Battle

Battle was a Confederate planter raised in Edgecombe County in the East. He had been a judge and Supreme Court justice, a cotton mill owner, banker, high church Episcopalian, scholar and founder of the UNC law school. He was a mighty defender of common law pleading.

Tourgée was a Yankee and former Union Army officer who had moved south after the war to Guilford County in the Piedmont. He was reviled as a carpetbagger and had recently relocated from Greensboro to Raleigh in order to escape the rancor of Greensboro’s white community. He was a failed manufacturer and nurseryman, a respected legal scholar, a founder of the North Carolina Republican Party, a popular author, a judge, the principal draftsman of North Carolina’s Constitution of 1868 and a crusader for racial justice – the originator of the phrase “color blind justice” and plaintiff’s counsel in Plessy v. Ferguson. He championed Code pleading.

Battle blasted: “No Southern lady should be permitted to sully her sweetness by breathing the pestiferous air of the courtroom.”

The Greensboro Patriot rejoined: “Blast the prejudice that puts women down as only fit to be men’s playthings!”

Albion Tourgee

In the end, Tourgée mounted a compelling argument in which he cited persuasive points and authorities, including Battle’s own legal treatise.

At the center of the swirling controversy was a demure but determined Quaker/Methodist maid – one who knew the law cold. Bar exams at that time were conducted orally by Supreme Court justices. Tabitha aced hers.

The Court ruled on the spot that she should be licensed. Tabitha marched home to Guilford County, then off in triumph to private practice in partnership with her brother in Dobson. The sun set slowly over the hills of western Surry County.

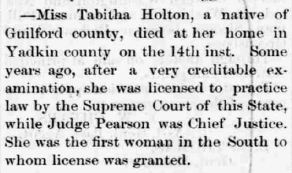

But wait. There is an epilogue. Tabitha practiced law only for eight years before she succumbed to tuberculosis at age 33. After her death, a handbill was distributed in Dobson. In part, it read:

Tabitha A. Holton, noble daughter,

Rest thou in thy immortal triumph. The power of thy genius has broken the iron bands of brutality which had been rivited [sic] for ages upon thy sex. No more can the barbed shaft of prejudice and envy reach thee in thy eternal repose. Thy genius stripped DEATH of all terror.

First in all the Sunny South to claim, and obtain, the full rights of womanhood. Death has crowned thy works; but a short space of time did eternity allot for thy mortality.

Tabitha was returned to Guilford County and laid to rest with her family in the cemetery at Springfield Meeting House. Her headstone reads, “Granted license in practicing law by the Supreme Court of N.C., January Term 1878, Died June 14, 1886.”

* * * *

Almost every detail set out above is factually accurate. The principal variance is that while William Horn Battle is acknowledged to have opposed Tabitha’s admission and made the statement quoted above, there is no confirmation that he was present at Tourgée’s argument before the Supreme Court. (See the Kelley Harris paper, Tabitha Anne Holton: First in North Carolina, First in the South for what can be confirmed.)

But this is after all, a fable – of tradition, change, and the role and status of women.

And, there is a broader point to be made: that, burdened by the weight of centuries of tradition and beset by towering cultural archetypes, Tabitha was a hero; and the legal profession provided the characters, the instruments and the path for her quest.

Major social change was achieved by moving from a general principle to its application in new circumstances. The way forward was guided by relevant points and authorities; and, ultimately, the victory was won by Tabitha’s unquestioned qualifications on the merits of her particular case.

A fable, I say. And a movie.

We are at a cultural moment.

We are at a cultural moment.